- Home

- Virginia Hume

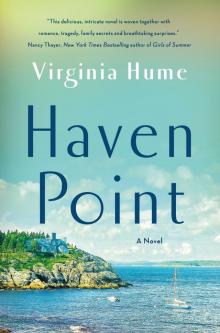

Haven Point

Haven Point Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my husband, Drew Onufer

PROLOGUE

August 2008

Haven Point, Maine

MAREN

Maren took her mug of coffee outside and sank into the wicker love seat. Skye would finally arrive the following day. Maren had so much she needed to tell her granddaughter. The conversation was long overdue, but Maren was still uncertain how to go about it, or even where to begin.

From the water came the sound of a horn, and Maren looked up to see a race underway. For the next half hour, she watched sailboats fly across the bay, white sails trimmed to harness the brisk breeze. The boats rounded their mark and went behind Gunnison Island, but from her perch high on the cliff, Maren could still catch glimpses of the mastheads when they emerged from behind clumps of spruce, like stealthy hunters gliding between coverts.

The cannon shot signaling the end of the race startled Maren from her reverie. She had been like this since her daughter died six months earlier, wavering between agonizing grief and a strange fugue state. Most days she had found herself sitting in this very spot for hours, just staring out at the water.

If Georgie was right (and she usually was), the hurricane barreling toward the coast could cause problems on Haven Point. It was hard to imagine, given the crisp air and sapphire sky today, but Maren had spent enough summers here to know how quickly the skies could change. With no more effort than it took to wipe a cloth across a dusty shelf, a storm could mock their efforts to tame this wild peninsula. Go ahead. Build your roads. Carve your paths. Plant your gardens. Never forget who’s really in charge, though.

She and Skye would be fine in Fourwinds, of course. The old house had faced down plenty of weather in its day.

Maren sat listening to the ocean engaged in its violent, noisy, age-old battle with the rocks below. That strangely pacifying sound was the heartbeat of this house. She’d always thought of Fourwinds as a living thing—pulsing, thrumming, speaking to her. She had loved it from the first, even when she so mistrusted the community outside its doors.

Skye did not know it yet, but Fourwinds would be hers someday. Maren had planned to leave it to both her children, but a few years earlier, Billy had made his wishes clear.

“I love it there, but I’ve lived abroad my whole adult life. Let Annie have the house,” he’d said.

“She wouldn’t want it.”

“You never know,” Billy replied with a gentle smile. “She just might decide to come back to Haven Point someday.”

Billy had been right. In the end, the very end, Annie had wanted to come back.

Her granddaughter did not know this yet either. After the memorial service, Skye had asked what they would do with the ashes. “We can figure it out later,” Maren had said. Skye had been satisfied. She had no reason to imagine her mother—flaky on her best day, downright reckless on her worst—had left detailed instructions on that (or any) subject. There was so much Skye didn’t understand about her mother.

Maren rose and went inside to the living room. Her eyes took in the books, trophies, and pictures that crowded the shelves. They were all there, the Demarest women, layered over one another like a fossil record. Even Annie. Her daughter might have abandoned this house, but Fourwinds had not returned the favor. She was everywhere: her name next to Charlie’s on the Stinneford Cup trophy, her face in photographs, her soul in paintings and drawings.

And she lived on in Skye, too. Maren smiled at the memory of Oliver’s reaction all those years before, when Annie told them she had decided to have a baby.

“Ah, artificial insemination.” Oliver had nodded in his doctorly way, as if she had told him she planned to try a new heartburn medication. “What an interesting idea. Do clinics provide this service to single women?”

“I think so. I’m still looking into it,” Annie had said breezily. “If not, Flora said she would pretend she’s my lover.”

How Oliver had not fallen out of his chair at that moment, Maren would never know. But of course, he was careful with Annie, after everything that happened. They promised to love Skye, to do all they could to help raise her. They hadn’t realized what they were signing up for, but it never mattered. From the first moment, they were so beguiled by the little redhead, they would have cheerfully laid down their lives for her.

Still, Skye saw Haven Point as her mother had: beautiful on the surface, petty and snobbish underneath. Maren understood; she had once felt just the same way. It was only in the worst moment of her life that she realized what she’d missed. Just as the big storms wiped out Haven Point Road, exposing the bedrock beneath, it had taken grief and pain washing everything away for Maren to finally see the community’s sturdy foundation, its titanic heart.

Maren recalled a maxim Annie used to share with her art students at the start of each semester: Everything depends on the quality and direction of light. It was only in the last year that Annie had finally applied this lesson to her own life, that she relinquished the story she had clung to for so long, about what had happened here and who was responsible. By then, it had been too late.

But it was not too late for Skye.

CHAPTER ONE

August 1994

Washington, D.C.

SKYE

Skye Demarest had ten minutes to decide whether to lie to her best friend.

Skye didn’t like to lie, but if the choice was between honest and normal, she was obviously going to pick normal every time. As far as she was concerned, that was just survival.

The trick was knowing what qualified as normal. In Skye’s experience, the definition was pretty slippery.

When she was little it was so much easier. Back then, Skye didn’t have to lie, because she thought she was just like every other kid. That lasted until the summer after first grade, when Gretchen Hathaway clued her in.

Skye and Gretchen were both attending the little day camp at the community center. One day, Gran showed up at the edge of the playground and called Skye over.

“Hi, love. Your mom needs to go away for a bit, so I’m taking you up to Haven Point with me this afternoon. I’ve let the camp director know.”

Skye had looked away and tried not to cry.

“You need to get your things,” Gran said kindly. “I’ve packed your suitcase already.”

Gretchen had followed Skye into the building. (She told the counselor she was going to help her friend, but she just stood there and watched as Skye shoved things into her backpack.)

“Where are you going?” Gretchen asked.

“Up to Maine with my grandmother,” Skye said.

“Why do you have to go all of a sudden?”

She felt a nervous bubble in her stomach. This was not the first time Gran had showed up out of the blue and taken Skye somewhere. She just hadn’t thought to question it before. When she saw the this is weird look on Gretchen’s face, though, it hit her: It was weird. Normal people know about vacations ahead of time! They tal

k about them and make plans!

The honest answer to Gretchen’s question was “I don’t know,” but some voice inside told her that the reason, whatever it was, needed to stay a secret.

It was amazing, how easily the lie slid out of her mouth. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a very good one.

“My mom is sick. Gran is taking me so she can get better.”

“What’s she sick with?”

Skye scrambled to come up with something bad, but not too bad.

“She has to get her tonsils out.”

Gretchen was an absolute pro at using her face to make people feel inferior. All she had to do was tuck her chin and scrunch her eyebrows, and I think you’re weird turned into I think you’re lying.

It got worse when Skye came home from Maine and ran into Gretchen and Emily Walker at the park. (Emily was like a little trained poodle who followed Gretchen everywhere and obeyed all her orders).

“While you were gone, my mom brought a casserole to your house,” Gretchen said accusingly. “She said your mother wasn’t even home.”

Skye felt her face get red. It wouldn’t have been as bad coming from anyone else, but Skye worshiped Gretchen’s mom. Mrs. Hathaway was the room mother and the Brownie troop leader. She had pretty brown hair, perfect clothes, and bubbly excitement about whatever her kids were doing.

Skye fantasized about her all the time. She’d imagine herself on a chilly night, curled up on the Hathaways’ front stoop. Mrs. Hathaway would open the door and find her there.

“Oh no. Oh, my dear Skye!” she would say, her eyes filled with worry, as she scooped Skye up and brought her inside. (Skye always pictured herself really quiet and stoic throughout the ordeal, so while Mrs. Hathaway was obviously deeply concerned, she also admired Skye for being so calm and brave.)

Skye never mentally sketched out why she was on the Hathaways’ doorstep. She didn’t want to imagine her mother dead (or to even make her the bad guy), so she just left her out entirely. She wrote the rest of the Hathaway family out, too, while she was at it. She barely knew Mr. Hathaway, and it totally broke the spell to imagine Gretchen or her little brother there.

Despite the unsatisfying holes in the story, it had been Skye’s favorite fantasy. When things were bad at home and she couldn’t sleep, she’d replay it over and over in her mind until she felt calmer.

Skye was so humiliated by the idea that Mrs. Hathaway knew she lied about her mom’s tonsils (or, worse, that things at Skye’s house were “not normal”), she could barely speak. She mumbled something about her mom staying with a friend then walked away, cheeks still burning, while Gretchen and Emily whispered about her.

Of course, Skye’s lesson from the experience was not that she should tell the truth. She just needed to get better at lying. That was one good thing about constantly changing schools. Just when she felt like a lie was about to catch up with her, her mom would get a new teaching job at another nearby private school. Since Skye’s tuition was always part of the bargain, she had to go with her. New school, new and improved lies!

She still had close calls, like two years earlier in sixth grade when Max Zilkoski asked who her dad was. Skye gave him her usual answer.

“He died in the war,” she said, then looked down sadly. (Until third grade, she’d just said “He died,” but kids started asking “How?” so she’d added the war part.) The sad look was key, because it made people uncomfortable, and they stopped asking questions. Unfortunately, Max was book smart but people dumb, so he missed his cue.

“Which war?”

Skye froze. Her many schools with different history curriculums had given her an encyclopedic knowledge of the Revolutionary War and Civil War (and, weirdly, the Peloponnesian War). However, in a panicky search through her brain for some war that had happened since she was born, she found a gaping hole where twentieth-century military history should be.

“The Cold War,” Skye replied, finally. She tried to sound certain, though she had a sneaking suspicion the answer wasn’t quite right, and Max’s confused expression was not comforting. But then he suddenly got excited.

“Wait, was he a spy?”

Once again, Skye was dumbstruck. Fortunately, at this point Max’s social cluelessness came in handy. He assumed the answer was classified.

“I get it. You can’t talk about it.” He nodded knowingly.

The next month, Skye’s mom announced she’d accepted a job teaching art at some hippy-dippy school in Maryland. Skye was a little bummed, since she had just started making friends, but at least she could quit worrying about whether Max Zilkoski could keep a state secret.

Now, once again, she was being whisked off to Haven Point. The situation wasn’t exactly the same as that time with Gretchen, though. First, Skye didn’t know what was going on back then. Now she did. In fact, she knew it so well, she’d been able to hide it.

Skye’s grandfather had died in May, just six weeks after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Gran had kept a close eye on her mom after that, looking for any hint a relapse was coming. Instead of leaving for Maine over Memorial Day weekend, like she usually did, she stayed in her apartment, just a mile from Skye and her mom. If Skye’s mom had gone off the rails then, Gran would have figured it out first, like she always had.

Skye also knew the signs that Anne was about to start drinking again, but it wasn’t until Gran left for Haven Point in early July that she began to spot them. At first it was just exaggerated versions of her normal behavior: staying up later at night, hanging out with sketchier friends, acting more irritable than usual.

The sure sign was when she stopped feeding the birds.

Keeping seed in the bird feeder was the one household task her mom normally stayed on top of (at least partly because it didn’t have to be done at an exact time—“lunch at noon” was way too specific, but “birdseed low” she could handle).

Resisting the temptation to fill it herself, Skye watched the bird feeder as if it were a countdown clock. The seed level got lower and lower, and sure enough, soon after it was empty, bottles started appearing in the trash outside.

Skye knew she should tell Gran her mom was drinking, but she also knew if she did, Gran would take her up to Haven Point, which would blow up all of her plans with Adriene for the rest of the summer. So, she kept it a secret. If the phone rang when her mom was drinking, Skye would race to get it. If it was Gran, she’d say her mom was out with one of her non-sketchy friends, or doing some other Sober Mom–sounding thing.

Skye was used to doing everything herself anyway, so it worked out fine. Well, until Gran called the night before, while Skye was out. First thing in the morning, Gran had showed up at the house and gone straight to her mom’s room. She came out a half hour later and found Skye in the living room.

“Skye, your mom needs help, as I suspect you know. I’m taking you to Maine tomorrow morning. I need a few hours here, though. Can you go somewhere for a bit?”

Skye felt a little guilty, seeing how tired Gran looked, but she steeled herself with the reminder that this was just what she’d been trying to avoid. She rose from the love seat and marched to the front door.

“I’m going to Adriene’s,” she’d said, slamming the door shut behind her.

Now, as Skye headed through the swampy heat to her friend’s house, she considered the other big difference between this situation and the one years before: Adriene was nothing like Gretchen. Skye had known that since they first met, the summer before.

Skye had been at the pool when a girl about her age walked up and asked if the lounge chair next to her was taken.

“I don’t think so,” Skye said.

Skye, who had to sit under an umbrella, because her skin would fry in about five minutes otherwise, watched with envy as the olive-complexioned girl angled her chair to face the sun. Once she was situated, she turned to Skye.

“I’m Adriene, by the way. My family just moved into the neighborhood.”

“Nice to meet you

. I’m Skye.”

Before they could say anything else, a little girl appeared. She wore a shiny purple bathing suit and huge mirrored sunglasses. She looked like a mini-Adriene—with the same complexion, and thick, almost blue-black hair.

“What do you want, Sophia?” Adriene asked.

“Natalie says she gets to name the baby turtle.”

“So, let her,” Adriene replied.

“But I want to name it!”

“Oh my God, Sophia,” Adriene said wearily. “Go back to the baby pool. Seriously.”

“Okay, but I’m telling Natalie you said I could pick the name!”

“Fine.” Adriene sighed. Sophia turned on her heels and marched back to the baby pool.

“Sorry. My sister’s a lunatic,” Adriene said.

“Who’s Natalie?” Skye asked.

“Sophia’s imaginary enemy.”

“She has an imaginary enemy?” Skye laughed.

“Yeah. Natalie’s supposedly really mean, but I hear how Sophia talks to her. I can’t blame her.”

“And the baby turtle?”

“Also imaginary.”

Over the next half hour or so, Skye picked up some key facts. Adriene Maduros was one of six kids. Her family had moved into D.C. from Rockville, Maryland. She went to a school way out in Virginia (“super-strict Catholic, the closest my parents could find to Greek Orthodox”) that sounded like the complete opposite of Skye’s. It left them in the same position, though: open to friends outside of school.

When Skye spotted Gretchen Hathaway at the sign-in desk, her heart had sunk.

That’ll be the end of that, she thought.

As usual, Gretchen looked like she’d jumped off the set of Beverly Hills, 90210, with her wispy blond bangs and her white denim overall shorts (one side of the bib unbuckled, obviously).

Skye had left public school in second grade, when her mom got her first teaching job. Eventually, most of the neighborhood girls also scattered to various private schools, but the posse got together over holidays and in the summer, and Gretchen was still totally in charge.

Haven Point

Haven Point